Carbon Offsets. The Good, The Bad and The Ugly

When booking an international or domestic flight, airlines encourage passengers to invest a little money in carbon-saving technologies to offset the CO2 emissions combusted by the jet’s turbines.

Corporations and governments are doing the same thing, investing in green technologies, often in developing countries and placing the carbon savings into the positive side of their ledger as a credit. These offsets are emerging as a billion-dollar business worldwide and growing exponentially.

Are these carbon offsets worthwhile? Is there value for money? The literature on the value of offsets is mixed. Projects that are Good, Bad, or Ugly are described below.

Briefly, well-managed cap and trade programs are good. Bad carbon offset projects include technologies that pretend to be green but are not. Corporations and governments purchasing hot air only for greenwashing are Ugly.

Firstly, let’s take a quick look at the terminology for this market.

Definitions

A carbon offset is a reduction or removal of carbon dioxide emissions or other greenhouse gases to compensate for emissions made elsewhere. A carbon credit is a transferrable instrument certified by governments or independent certification bodies to represent an emission reduction of one metric ton of CO2 or an equivalent amount of other greenhouse gases (GHGs).

Globally, there are numerous trading frameworks driving offset and credit markets. The European Union Emissions Trading System (EU-ETS) covers over 40% of European greenhouse gas emissions. California’s cap-and-trade program covers about 85% of statewide GHG emissions.

Carbon credits work like permission slips for emissions. When a company buys a carbon credit through a government-run cap and trade program, it gains permission to generate one ton of CO2 emissions. Offsets through private company transactions flow horizontally, trading carbon revenue between companies. “When one company removes a unit of carbon from the atmosphere as part of their normal business activity, they can generate a carbon offset. Other companies can then purchase that carbon offset to reduce their own carbon footprint.”

In voluntary carbon markets, companies or individuals use carbon offsets to meet self-defined goals for reducing emissions. Credits are issued under independent crediting standards. Offsets are a popular tool for companies to declare publicly that their net zero goals are being achieved, even when they continue to pollute.

California (Quebec) Cap and Trade System

2013 Québec set up a cap-and-trade system for greenhouse gas emission allowances. The following year, the province linked this initiative to California’s carbon cap and trade program. This carbon trading market is the largest in North America. It has generated $7.3 billion in revenues. These monies provide financial support to Quebec companies, municipalities, institutions, and citizens for transitioning to a low-carbon economy.

Quebec is evaluating this program through “a series of government-sponsored workshops to solicit input from interested parties and the public at large.”

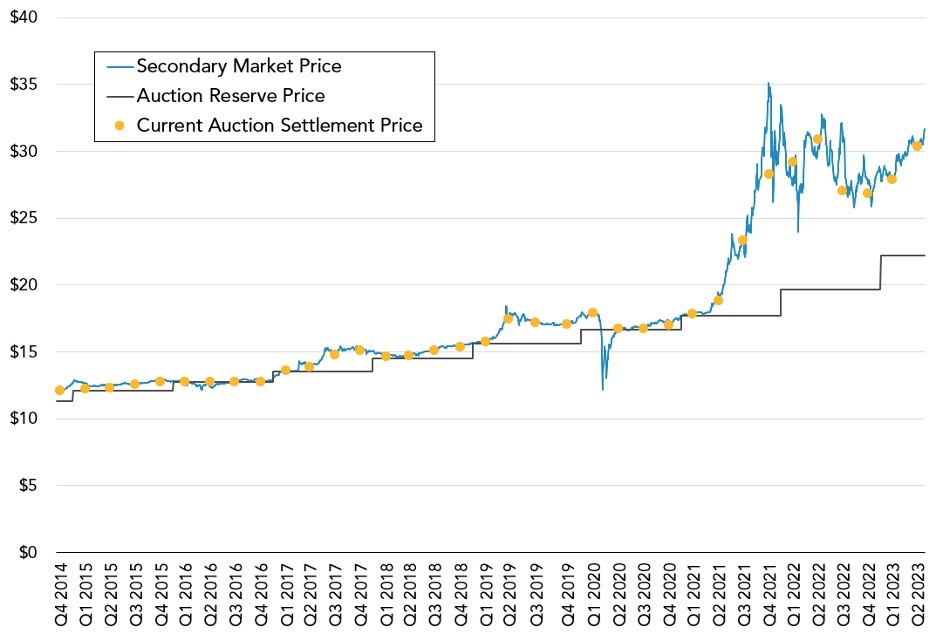

Since 2012, The California cap and trade auction prices have been above or near the reserve price. “Under the cap-and-trade program, the steadily declining cap on emissions helps California’s public and private energy producers to meet carbon dioxide emissions reduction goals set by the state legislature. Actual emissions have been below the cap in each compliance year.”

Figure 1: California Cap and Trade Carbon Allowance Prices

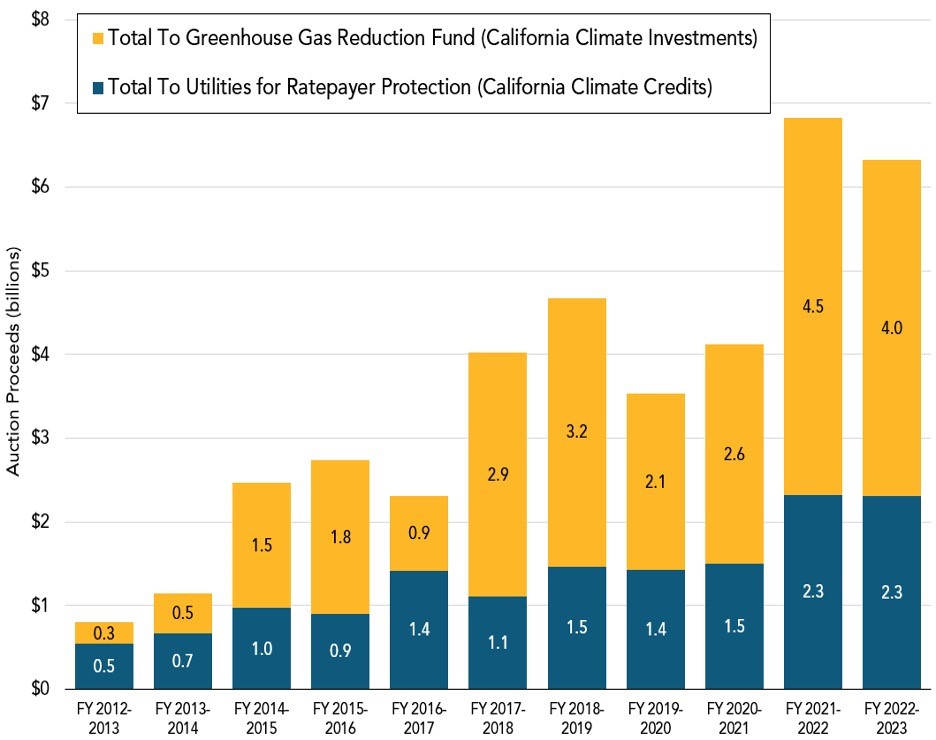

Figure 2 illustrates the vast amounts of money that California is investing in green technologies through its cap-and-trade program. In FY 2021/22, $4.5 billion was invested. In FY 2022/23, this amount was $4 billion. The trend is sloping upward over the past decade.

Figure 2: California Auction Proceeds by Fiscal Year or Auction Quarter

Are Carbon Offsets a Scam?

Offset and credit programs are an important tool for countries to meet their Nationally determined contributions (NDCs) commitments and achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement at a lower cost.[1] Is this a scam?

The following few paragraphs show the g\Good, the Bad and the Ugly of carbon trading.

The Good

Both private carbon trading and government cap and trade programs raise vast sums of money earmarked for investments in green and carbon reduction technologies. The California (Quebec) cap and trade program illustrates a successful program. In addition to helping finance billions of dollars for green technologies, the program is reducing overall emissions by slowly tightening the caps on allowed emissions.

Private sale offsets could potentially work well. Airline customers buying offsets to raise money for growing a mangrove forest in Indonesia is “good.” Mangroves absorb considerable amounts of carbon. These savings legitimately allow government companies or government to offset their net carbon emissions.

Carbon offsets for financing renewable energy technologies is similarly “good”. Examples include small or moderate-sized hydro faculties, run-of-river power projects, and geothermal, solar and wind power.

The Bad

The European Union (EU) 2016 commissioned a study on the success of its offset initiatives. The report concluded that emissions reductions were overestimated for three-quarters of the offsets from 2013 to 2020 under the EU’s carbon trading scheme. Well-managed cap and trade programs are important to the climate remediation toolbox. The system only works with pristine carbon reporting. There is no place for voodoo carbon accounting or hyping the books.

For air travel customers that have purchased offsets, the airline emissions have already been spewed. The offsets may reduce future emissions, but they “won’t remove what’s already been emitted. The offsets only “cancel out” what has already been emitted, at most. “Offsets don’t reduce emissions, and it’s about keeping things the same.”

Suppose offsets targeted for forestry growth were lived short-lived, and after a moderate period, logging activities started up, possibly involving clear-cutting. The carbon emission savings would be illusionary.

Another “bad” example involves investing in a wood pellet plant. Wood pellets are chain long-chain hydrocarbons and heavy polluters.

Investing in carbon capture utilization and storage technologies may be either good or bad, depending on the nature of these projects and the intensity of upstream emissions.

CO2 is captured and stored with CCS, keeping it out of harm’s way. The sequestration stops the CO2 from warming the climate, which is good. There are numerous hurdles for a successful CCS operation. These include capture efficiency, the availability of storage sites and high costs. These hurdles carry a heavy upstream carbon load, “but perhaps CO2 leakage from the storage site is the most worrisome of all the potential risks.”

There is a very small chance that CO2 pumped underground may escape through multiple channels, such as fractures in the geological cavern where it is stored.

CO2 stored in both active and abandoned wells are possible pathways for leakage. Well, leakage takes place either continuously or from well blowouts. “Continuous leakage is a slow leakage that happens as a result of improper well construction, such as failures in casing or cement degradation. Well blowouts are abrupt incidents when the pressure control fails.”

The Ugly

Writer George Monbiot compared carbon offsets with the ancient Catholic church’s practice of selling indulgences: absolution from sins and reduced time in purgatory in return for financial donations to the church. These indulgences allowed the rich to feel better about their sinful behaviour without changing their ways. Ugly involves companies or governments greenwashing their operations to appear green when the opposite occurs.

An investigation by The Guardian revealed that over $1 billion of carbon credits certified by leading platform Verra could be worthless. The publication concluded, “The forest carbon offsets approved by the world’s leading certifier (Verra) and used by Disney, Shell, Gucci and other big corporations are largely worthless and could worsen global heating. More than 90% of their rainforest offset credits – among the most commonly used by companies – are likely to be phantom credits and do not represent genuine carbon reductions”. This is Ugly.

Conclusion

Offsets generate a lot of cash which is put to good use for green projects. These projects generally have lasting long-term benefits but don’t immediately lower emissions. Offsets are legitimately criticized for not providing an immediate net carbon reduction. Other criticisms involve poor carbon accounting and the possibility that some projects might have gone ahead, even without offsets support.

The government-sponsored cap and trade programs provide both needed cash for green projects and lower emissions through declining caps, albeit slowly. On balance, these are The Good. Bad examples involve projects that never get off the ground or, in the case of an investment in forestry, the land use changes through logging or switching to farming, cattle or tourism.

Carbon capture utilization and storage are complicated. It is sometimes Good, sometimes Bad, and potentially Ugly. Greenwashing by corporations and governments (exaggerating the benefits and erroneously declaring net zero) is Ugly.

On balance, a well-managed cap and trade program is preferable to a carbon tax regime, especially in the Canadian context, where most of the proceeds from the carbon tax are redistributed back to lower and middle-income households. This redistribution has social benefits, but its impact on carbon reduction is minimal.

Ken White is a semi-retired economist living in Port Coquitlam, British Columbia. His recent work has been modelling the economic

impacts of the green economy and defence-related innovation. Also by Ken White The Bank of Canada – Is it Broke or Broken?