Monetary Policy During the Pandemic and Beyond

Monetary policy and its approach to fighting inflation have radically changed over the past twenty years, and many question whether it works.

Many households and businesses are hurting from high-interest rates, yet inflation is still too high.

This article traces the developments of how monetary policy has changed during the pandemic years and comments on its efficiency in fighting inflation. Key sources are the International Monetary Fund regarding the changing monetary policy of central banks and its recent world economic outlook.

Today’s inflationary and financial environment differs from earlier years, e.g., during the Great Depression in 2008 and beyond.

These “differences” are summarized below.

- During the 2008 Great Depression, the core problem was not rising prices but possible weak demand leading to deflation. Central banks developed policy tools providing additional stimulus.

- “Central banks were becoming emboldened to pursue policies that simultaneously met the need for further stimulus and achieved social objectives, such as hastening the green transition or promoting economic inclusion.”

- Currently, public debt is high in most advanced economies. Higher interest rates are fighting inflation. The blade cuts from both sides for these higher rates as deficit-heavy governments now pay higher carrying costs for their debt.

- Governments hate higher interest expenses. They would prefer that central banks cooperate by monetizing their debt—that is, by purchasing government securities private investors won’t buy.”

- The nature and frequency of economic shocks are changing. In addition to shocks in aggregate demand, there are now many shocks: “demand versus supply, specific risks versus systemic risks, transitory versus permanent. It is difficult to identify the true nature of these shocks in time to respond.”

- Monetary policies are starting to take a back seat in managing these complexities.

- The economic environment changed dramatically during the COVID-19 crisis. Government spending rose exponentially. In Canada and the United States, the federal governments provided massive and highly concentrated financial support to businesses and households.

Is it Working?

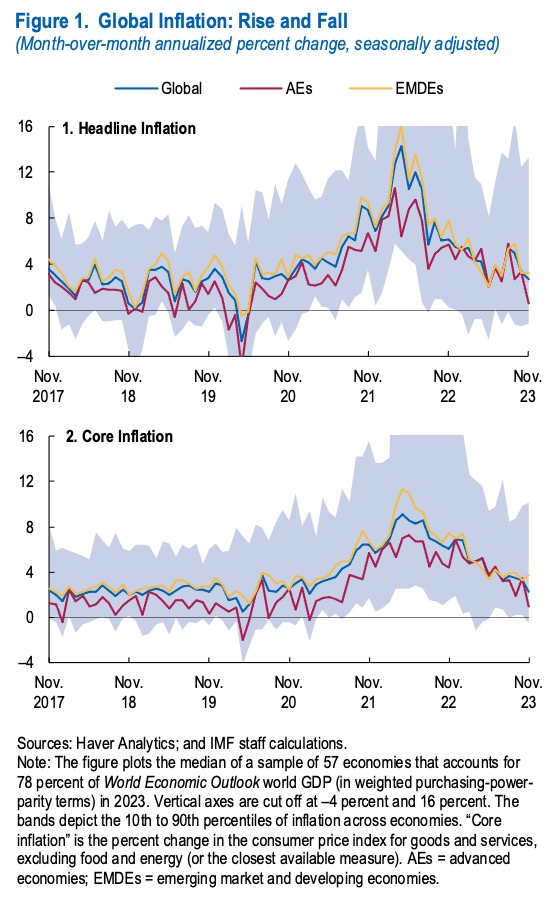

According to the IMF World Economic Outlook for January 2024, the answer is yes, although serious risks are evident. Inflation has been falling faster than expected. Recent monthly readings for headline and underlying (core) inflation are near the pre-pandemic average (Figure 1).

The subsiding inflation reflects lower energy prices––and its associated pass-through to core inflation. Labour markets are less tight; job vacancies are declining, and unemployment rates are moderately increasing, although still relatively low.

Wage growth is contained “with wage-price spirals—in which prices and wages accelerate together––not taking hold. Near-term inflation expectations have fallen in major economies, with long-term expectations remaining anchored.”

IMF Inflation Outlook

Global headline inflation is expected to fall from 6.8 percent in 2023 to 5.8 percent in 2024 and 4.4 percent in 2025. Advanced economies are expected to see faster disinflation.

For those economies with an inflation target, headline inflation is projected to be 0.6 percentage points above the target by the fourth quarter of 2024. Most of these economies are expected to reach their targets (or target range midpoints) by 2025.

Risks and Wild Cards

Slower-than-assumed withdrawal of fiscal support: fiscal policy support may be withdrawn more slowly than assumed during 2024–25. This would exacerbate inflation and higher borrowing costs.

Commodity price spikes amid geopolitical and weather shocks: The conflict in Gaza and Israel could escalate further into the wider region. Continued attacks in the Red Sea (11 percent of global trade flows), as well as the war in Ukraine, could cause adverse supply shocks to the global recovery.

Persistence of core inflation, requiring a tighter monetary policy stance: A slower-than-expected decline in core inflation in significant economies due, for example, to persistent labour market tightness and renewed tensions in supply chains could trigger a rise in interest rate expectations and a fall in asset prices, as in early 2023.

Such developments could increase financial stability risks, tighten global economic conditions, trigger flight-to-safety capital flows, and strengthen the US dollar, with adverse consequences for trade and growth.

What does it all mean?

- Monetary policy has changed substantially in the pandemic and post-pandemic periods. The priority continues fighting inflation by increasing interest rates. However, the Quantitative Easing initiative during 2020 and 2021 provided governments with cheap money, which was used to balloon up deficits.

- When tightening, central banks must fully know its impact on increasing deficit-carrying costs for governments addicted to high deficits.

- Despite these fiscal endurances, the IMF has concluded it is a monetary policy.

- We are working globally to lower inflation, especially in advanced economies. The reason is twofold. Firstly, lower energy costs, which have nothing to do with monetary policy, have reduced headline and core inflation.

- Secondly, fiscal deficits in advanced economies are on the decline. Inflation targets are likely to be achieved in the most advanced economics.

- The IMF has emphasized severe risks in these inflation targets being met. These risks mainly focus on the need for fiscal policies to reduce their primary deficits.

___________________________________

Ken White is a semi-retired economist living in Port Coquitlam, British Columbia. His recent work has been modelling the economic impacts of the green economy in British Columbia and other provinces. Previously, when working for the Federal Government in Ottawa, Ken worked extensively with its financial management system and the federal Main Estimates. Ken maintains a strong interest in fiscal and monetary policies and issues.