Urban heat islands leave cities sweltering

By Tim Radford

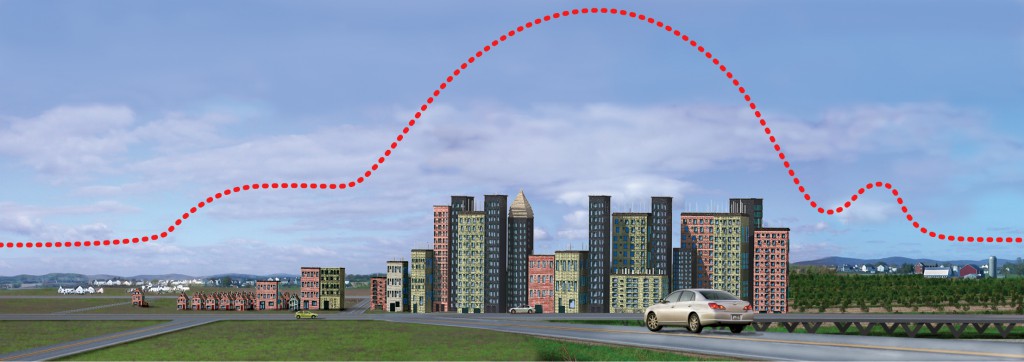

LONDON, 1 June, 2017 – Many of the world’s great cities are about to feel the heat. A characteristic of inner cities is that they are inevitably warmer than their hinterland. And when the cost of this urban heat island effect is taken into account, the bills for climate change go up.

The total economic costs of climate change for cities could be 2.6 times higher because of this urban heat island effect. And for some cities, by the end of the century the climate change losses could reach 10.9% of gross domestic product – compared with a global average of 5.6%.

Most cities are measurably hotter – thanks to the traffic, the infrastructure, the central heating, the air conditioning, industry, and the asphalt and brick and cement and tiles – than the countryside beyond.

So if global average temperatures rise by 2°C by 2050, then many cities will be 4°C hotter, on average.

Cities cover just 1% of the planet’s surface. But they produce 80% of the world’s wealth, they consume 78% of the world’s energy, and by 2050 they will be home to 65% of the planet’s population. So what happens in cities matters in all calculations of global warming.

Containing the heat

Researchers from the UK, Mexico and the Netherlands report in the journal Nature Climate Change that they analysed the urban heat island effect for 1,692 of the world’s cities between 1950 and 2015, made an assessment of the possible costs and looked at some of the things civic authorities could do to contain urban warming.

Some of the biggest cities may have the quietest voice in strategies to limit climate change, but they are the population centres that are the focus of greatest danger.

Studies have already underlined the cost to economies and the periodic hazard of lethal heat waves driven by manmade global warming. Other researchers have identified particular costs to be imposed on cities by climate change as nations try to keep cool.

And separate studies have examined the impact of sea level rise on coastal cities – and many of the world’s greatest cities are on estuaries – in Europe, the United States and worldwide.

“Any hard-won victories over climate change on a global scale could be wiped out by the effects of uncontrolled urban heat islands”

But the authors see their study as a different approach: heads of state and ministers talk about mitigating global warming by international effort, but their concern is – what can be done at the local level?

Other research has made the obvious point that green foliage and water absorb less heat than asphalt and concrete. The latest study puts figures to the foreboding: in the 67 years since 1950, 27% of the selected cities and 65% of the urban population have experienced more warming than the world average: 60% of the urban population experienced warming twice as large as the world as a whole.

“Any hard-won victories over climate change on a global scale could be wiped out by the effects of uncontrolled urban heat islands,” said Richard Tol, an economist at the University of Sussex in the UK, and one of the authors.

“We show that city-level adaptation strategies to limit local warming have important economic net benefits for almost all cities around the world.”

Impact underestimated

So pavements that reflect more sunlight, and “green” roofs and greater growth of parkland and tree canopy in cities could make a significant contribution.

Change 20% of the roofs and half the pavements to the cool forms, and the savings would be 12 times the cost of installation and maintenance, the authors say. And in doing so, city engineers would reduce air temperatures by 0.8°C.

“It is clear that we have until now underestimated the dramatic impact that local policies could make in reducing urban warming,” Professor Tol said.

“However, this doesn’t have to be an either/or scenario. In fact, the largest benefits for reducing the impacts of climate change are attained when both global and local measures are implemented together.

“And even when global efforts fail, we show that local policies can still have a positive impact, making them at least a useful insurance for bad climate outcomes on the international stage.” – Climate News Network