The True North, Strong and Ice-Free – An Update

This report, “The True North, Strong and Ice-Free” was originally published on GLOBE-Net on February 25, 2015. This report has been updated by Ken White, a semi-retired economist from Port Coquitlam, British Columbia to reflect the new realities of the North and the policy implications of these new realities. Ken has previously worked on northern development, transportation and Arctic issues both as an economist for the federal government and as a consultant for the National Research Council and Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

This report, “The True North, Strong and Ice-Free” was originally published on GLOBE-Net on February 25, 2015. This report has been updated by Ken White, a semi-retired economist from Port Coquitlam, British Columbia to reflect the new realities of the North and the policy implications of these new realities. Ken has previously worked on northern development, transportation and Arctic issues both as an economist for the federal government and as a consultant for the National Research Council and Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

GLOBE-Net, August 13, 2020 – It’s not a matter of whether ice-free navigation of the Arctic Ocean will be possible. The issue is how soon this will happen and to what degree.

Opinions vary as to how soon ice-free navigation may be possible, but studies by the U.S. Office of Naval Research (ONR) reveal that summer sea ice levels could potentially fall to zero before the end of this century, which would mean that the Arctic Ocean would be completely open, something unprecedented in living memory.

The impacts of an ‘open waters’ Arctic have ramifications that touch on a variety of issues – economic competitiveness, Arctic resource development, environmental impacts, sovereignty rights, national security, and impacts on northern communities and Indigenous cultures.

Canada’s role in the Arctic and our ability to exercise any influence in the management and protection of our northern seas are very much in doubt.

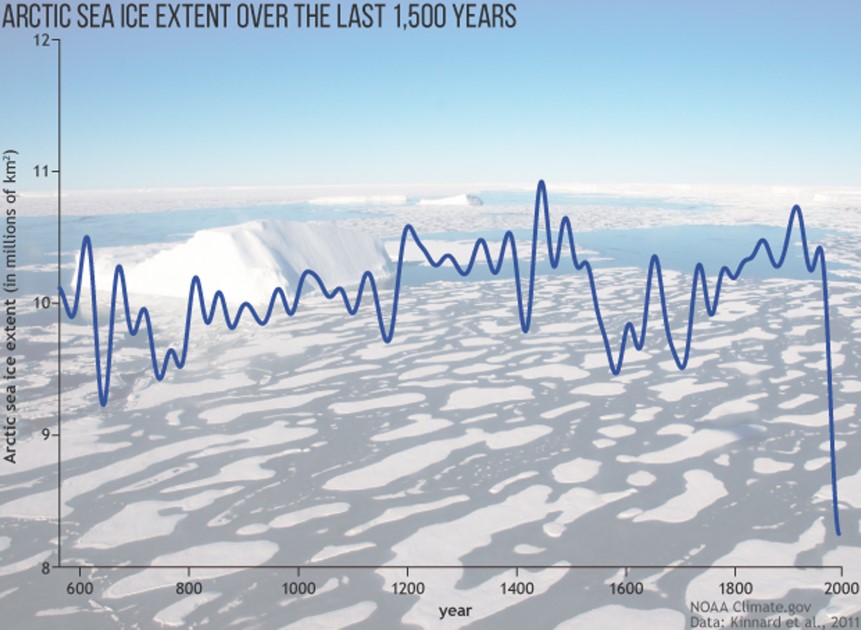

In the 2017 issue of the Arctic Report Card by the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) scientists reconstructed the changes and evolution of the Arctic sea ice over the past 1,500 years.

Figure 1 shows the Arctic sea ice over 1,500 years. There have been several periods when sea ice extents expanded and contracted. The decrease during the modern era is unrivalled. The decrease is also beyond the range of natural variability, implying a human component to the drastic decrease observed in the records.

Figure 1: Arctic Sea Ice Over the Last 1,500 Years

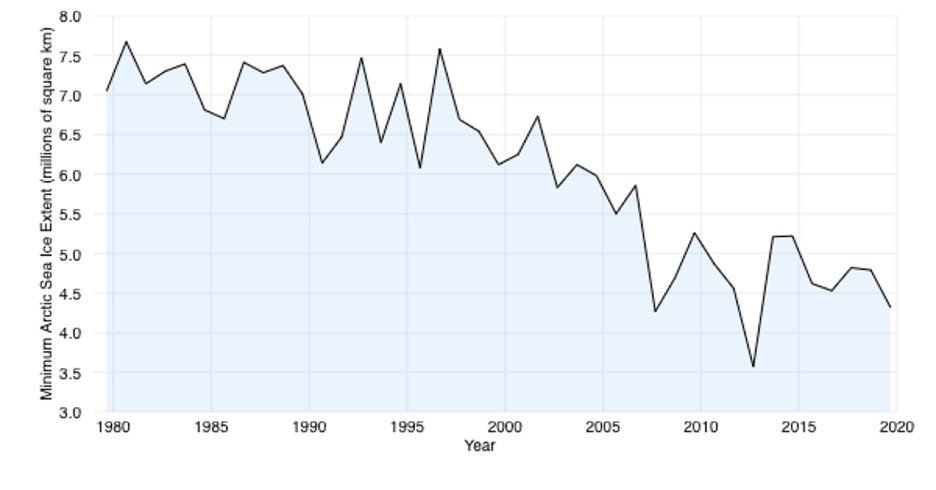

The area covered by sea ice in the Arctic expands and shrinks as the weather changes over the course of each season. The ice reaches its maximum extent in early March. With the spring sunlight and higher temperatures, the ice melts back reaching its minimum level by September.

According to NOAA, “through 2018, the downward trend for the summer minimum in September was 12.8 per cent per decade relative to the 1981–2010 average. Summer ice declines have been especially rapid since the start of the twenty-first century”. See Figure 2 on minimum sea ice in the Arctic from 1980 to 2020 (estimate) by NOAA.

Figure 2: Arctic Sea Ice Summer Minimum

Environment Risks

Using cleaner distillate fuels diesel including fuels and fuel oils is a simple way for ships to reduce harmful pollutants and particulate matter in the Arctic. Distillate fuels emit lower levels of sulfur oxides and black carbon.

In addition to distillate fuels, liquefied natural gas (LNG) is far cleaner. There are zero spill-related cleanup costs because it evaporates. LNG releases fewer air pollutants and almost no black carbon. It does release carbon dioxide and fugitive methane leaks would be especially harmful. As a result, the International Council on Clean Transportation does not consider LNG to be a long-term solution for Arctic shipping.

The International Council on Clean Transportation argues that hydrogen appears to be a promising solution for zero-carbon, long-range Arctic shipping. “Current barriers include limited supply, especially from sustainable sources, limited fueling infrastructure, and higher costs relative to other fuels, barriers that should lower over time.”

There are other environmental challenges looming on the Arctic horizon, not just from increased shipping, but also from potential exploration and development of oil and gas resources. The risks of major oil spills are very real and to-date the technologies and resources for cleanup and recovery, particularly in the extremely harsh operating conditions in frigid ice-choked waters are far from adequate.

In his book Future Arctic: Field Notes from a World on the Edge journalist Ed Struzik warns of the pending upheaval in the Arctic and what should be done about it. He writes “If there was a blowout in the Arctic and the oil got under the ice, powerful currents could carry the oil a long way into areas where whales, walrus, polar bears, sea birds, and fish thrive, This would be catastrophic to both the marine wildlife and to the Arctic’s subsistence economy.

“I think there should be a moratorium on offshore oil and gas development until the biological hotspots are mapped and protected, he said in a recent interview. “I also think that offshore oil and gas development should not proceed until engineers find a way of effectively separating oil from ice.”

Research, development and infrastructure in the Arctic

While policy statements surrounding Canada’s Arctic policy are forceful, actual investments made in Arctic navigation and communications infrastructure capabilities continue to be modest. The key reason appears to be the typically high cost of goods and services in the Arctic.

While infrastructure investments are only continuing at a modest pace, research on Arctic science has been growing in importance. “ArcticNet is a Canadian Network of Centers of Excellence that brings together researchers in the natural, human health and social sciences with Inuit organizations, northern communities, and federal, provincial and private sector agencies to study the impacts of climate change in the coastal Canadian Arctic.”

ArcticNet has funded “175 researchers from 33 Canadian universities, and 8 federal and 11 provincial organizations collaborate with scientists from 12 countries.” It has announced 30 new projects in 2019. There are five main themes including (1) marine systems; (2) terrestrial systems; (3) Inuit health, education and adaptation; (4) northern policy and development and (5) knowledge transfer.

In addition to the research by ArcticNet, federal scientists on the CCGS Amundsen are conducting marine science and some community-based work. The CCGS Amundsen is a Canadian research icebreaker for international collaboration in the study of the changing Arctic. The Amundsen conducted 1,300 days of dedicated scientific operations over 8 years or 163 days per year on average. It supported two major international overwintering studies in the Beaufort Sea and supported science teams from 15 countries. The research vessel visited all Canadian coastal Inuit communities as part of an international Inuit Health Survey.

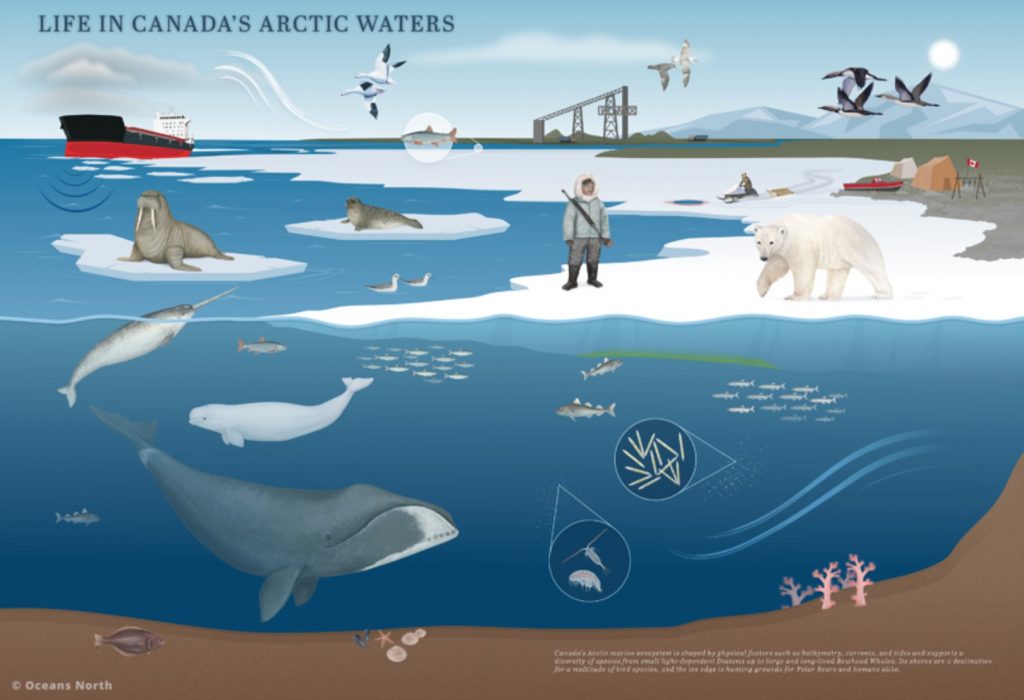

The changing and increasingly warmer climate is expected to increase maritime traffic in the Arctic as the melting ice results in more navigable waters. Yet, life in the Arctic is a precarious balance. Food is largely based on subsistence hunting and fishing. It is a natural circular economy and care must be taken by all to sustain this balance.

Warmer temperatures are threatening the Arctic food chain. Canada’s Arctic Marine Atlas produced by Oceans North illustrates this balanced and circular food chain. See Figure 3.

Economic Benefits

One of the more compelling shipping related imperatives relates to the economic factors associated with shorter sea routes between Europe and Asia. Despite the harsh operating conditions and higher risk factors, the economic benefits of the Arctic sea routes for both foreign and Canadian shippers are overwhelming.

There are two already well-established shipping routes along the northern coast, the most developed being Russia’s Northern Sea Route (NSR), which has received over 500 successful applicants, up from zero only five years ago. (See Arctic Shipping Routes Map)

The transit distance for a general cargo ship from Yokohama to Hamburg via the Northern Sea Route along Russia’s Arctic border is not only shorter than the alternative route through the Suez Canal but also offers considerable savings in time (reduced from 34 to 23 days) and in fuel costs, roughly estimated at US$200,000.

A ship sailing via the Northwest Passage (NWP) in U.S. and Canadian waters can shave 1,000 nautical miles off a voyage that would transit the Panama Canal, saving not only time and fuel costs, but also able to carry larger cargos free of Panamax depth restrictions, even after the Canal expansion has occurred. See the following. See Figure 4.

Figure 4: Northwest Passage

In 2013 the 225-metre long, 75,000 deadweight-ton Nordic Orion sailed from Vancouver to the Finnish port of Pori via the Northwest Passage with a full load of coking coal from Teck Resources to Ruukki Metals, a Finnish steel producer. Despite the hazardous conditions, this Panamax designed ship was able to carry 15,000 more tons of cargo than would have been possible via the Panama Canal.

In July 2019 Hurtigruten’s expedition cruise ship MS Roald Amundsen became the first battery-hybrid powered ship to sail over 3,000 nautical miles through the Northwest Passage.

Clearly, the harsh realities of the Arctic region are becoming less of an impediment to commercial shipping and tourism.

Shorter northern sea routes require less fuel, which translates into lower CO2 emissions from ships carrying heavier loads operating at slower more efficient speeds due to harsh Arctic water conditions. This benefit is accelerated substantially through the use of cleaner fuels rather than dirty bunker fuel.

Canada’s shipping policy

Canada’s sparse port and terminal services, modest ice-breaking support, quite rudimentary navigational guidance and ice pilotage, limited search and rescue services and inadequate oil spill response capabilities in the North have long been matters of concern to shipping experts.

The risks of an oil spill in Arctic waters and the limited capacity to respond to such an incident have been known for some time. (See report by the Pew Charitable Trusts on Becoming Arctic Ready

In a 2014 Discussion Paper issued as part of a review of the Canada Transportation Act (CTA), the Hon. David L. Emerson, P.C. stated that the Government of Canada did not expect the Northwest Passage to be a safe or reliable marine transportation route in the near future, due to multiple navigational challenges. However, improved conditions may mean that there will be more ships accessing the Northwest Passage for tourism, seasonal re-supply, research activities and natural resource exploration.

Both documents reasoned that the most significant threat from ships to the Arctic marine environment is the release of oil through accidental or illegal discharges, in part due to significant gaps in hydrographical data for major portions of the primary shipping routes necessary to support safe navigation.

A 2010 article on National Security and Canada’s Shipping Policy: We Can Do Better, by Dick Hodgson argued that should wish to be a leader in Arctic marine transportation operations it will have to make fundamental changes to our national shipping policies.

The almost complete dominance of commercial shipping in the Canadian Arctic by foreign flag vessels (apart from modest cabotage activities associated with community resupply), he notes, clearly heightens the threats to Canada’s Arctic security in all its forms – environmental, sovereignty, national security access to resources and impacts on Indigenous cultures.

The adoption of policy measures that stimulate ownership and operation of Canadian flag shipping above and beyond protected cabotage activities not only would contribute to enhanced security in all its forms, but would also stimulate expanded Canadian Arctic marine leadership and expertise

Sovereignty Issues

The Arctic is fundamental to Canada’s national identity. Canada’s vision for the Arctic has been to traditionally foster “a stable, rules-based region with clearly defined boundaries, dynamic economic growth and trade, vibrant Northern communities, and healthy and productive ecosystems.”

Getting along with our Arctic neighbours has been a major theme.

A July 2013 report summarizing Canada’s Key Accomplishments and Initiatives Exercising Our Arctic Sovereignty referenced Canada’s growing military presence in the region and the promise of increased funding for Coast Guard vessels and improved navigation. But it was short on hard facts of infrastructure spending.

A 2014 statement on military activities in the north asserts that “Canadian Armed Forces are active in the North 24/7, exercising sovereignty and exercising its capabilities to respond to any challenges that may arise.”

The Canadian government is currently re-thinking sovereignty and security in the Arctic. Its new Arctic and Northern Policy Framework is a profound change of direction for the Government of Canada.

The Arctic socio-economic and political environment is changing rapidly. Globalization, climate change and Indigenous rights are currently intersecting and framing the sovereignty and security agenda. Sovereignty and security in the Arctic have morphed from military defence, especially the protection of national borders and the assertion of state sovereignty over Arctic land and water, to a gentler and more collaborative concept involving economic, social, cultural and environmental concerns.

Sovereignty and security currently reflect new and distinct types of threats involving peoples, communities and their environments. There is a “growing recognition of the rights of Indigenous peoples to self-determination and the devolution of political powers to northern and substate governments, from Greenland to Nunavut to northern Scandinavia”

The emphasis now is to ensure Arctic people are thriving, strong and safe. The priorities are to:

- Nurture healthy families and communities;

- Invest in the energy, transportation and communications infrastructure that northern and Arctic governments, economies and communities need;

- Create jobs, foster innovation and grow Arctic and northern economies;

- Support science, knowledge and research that is meaningful for communities and for decision-making purposes;

- Face the effects of climate change and support healthy ecosystems in the Arctic and North;

- Ensure that Canada and our northern and Arctic residents are safe, secure and well-defended;

- Restore Canada’s place as an international Arctic leader; and

- Advance reconciliation and improve relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

The rapid warming of the Canadian North is affecting the land, biodiversity, cultures and traditions.

Issues of climate change, international trade and global security are intersecting. Melting sea ice is opening shipping routes and putting the rich wealth of northern natural resources within reach. This is bringing increased safety and security challenges that include search and rescue and human-created disasters.

This new partnership has strong implications for both Canada’s shipping policies and the ability of the Navy and the Coast Guard to engage in this current environment. The key priorities for Canada’s sovereignty and security issues for both the environmental and security aspects now give greater substance to community engagement and collaboration among international players.

National Security implications

There are even broader issues of concern for Canada’s presence in the waters that ring our northern frontier. A Special Study on the National Security and Defence Policies of Canada Standing Senate Committee on National Security and Defence published in March 2011 highlighted the bonanza of oil, natural gas, minerals, fish and other marine life that were opening up to a resource-hungry world as a consequence of the Arctic Ocean’s shrinking ice sheet.

It noted that access to resources and control of transportation routes – long considered matters of national security and points of contention among nations – were a leading cause of conflict and the Arctic was no exception. The report cited the Canada–US dispute over the Northwest Passage as a key case in point.

“Canada asserts that the Passage’s waters are internal, fully subject to our laws and regulations. The United States and many other countries say the Northwest Passage is an international strait, meaning that all nations have the right of so-called “innocent passage,” said the report.

While this is an issue over which our two nations have agreed to disagree, the broader international picture relates to what Arctic Ocean coastal states stand to gain from greater access to the Arctic seabed’s resources.

The five Arctic Ocean coastal states, including Russia, the United States, Norway, Denmark and Canada are determined to secure exclusive rights to a considerable area of the seafloor extending to the edge of their respective continental shelves. China has also shown strong interests in the Arctic. Read more.

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), states have ten years from the date of ratification to make claims to an extended continental shelf. Four of the five Arctic states Canada, Denmark, Norway, and the Russian Federation were to make known their desired claims by 2013, 2014, 2006, and 2007 respectively. Read more.

Since the United States has yet to ratify the UNCLOS, as a non-party to the convention, it cannot submit a claim under Article 76. Over the years, however, it has gathered and analyzed data to determine the outer limits of its extended continental shelf.

Conclusions

Although ice-free and open navigation through any of the Arctic passage routes may still be years away, accelerating change resulting from both global warming and increased industrialization are emerging on the horizon.

Ocean routes are opening up which in turn are resulting in substantially shorter distances to transport cargo, especially to Asian markets. Moreover, various projects planned or already underway by the Canadian government will also have a significant impact on commerce in northern waters.

Cruise ships are already operating in remote coastal communities, and deep-sea drilling is continuing in the Beaufort Sea, regardless of the lack of suitable infrastructure in place to manage a possible large-scale spill.

The potential industrial and economic benefits from new shipping routes, resource extraction, construction projects and Arctic tourism loom large, and the risks to the fragile Arctic environment arising from any increase in shipping and resource development activities are profound.

So too are the perils associated with ensuring access to the Arctic’s sub-sea bounty, protecting national sovereignty rights, and ensuring the safety of seaborne commerce.

The disappearing ice cover in the Arctic has revealed far more than the potentially navigable open waters. It has also revealed the enormity of the economic, social and environmental risks looming in Canada’s northern boundaries, risks that we are currently not well-equipped to manage.

The coming decade will evidently be a critical period for the change in the North on numerous fronts.